The ground is shifting in the global system of proxy voting.

Corporate and investment executives have vented occasional frustration with proxy advisers, the public-facing symbols of this system, for decades. In recent years, however, the sentiment has become much more steady than occasional, has refocused on the system rather than just on the proxy advisers as symbols, and has shifted toward a spirit of opportunity and not just frustration.

Today, corporate and investment executives have several clear views. The current proxy system has costs that exceed the benefits. It detracts from a long-term dialogue between investors and corporations and is one of the sources of short-term pressures of being a public company. And companies and investors can drive change to the proxy system because they are part of it.

Change will be difficult. Companies and investors disagree on the role and value of proxy voting, and it is all too easy to blame the proxy advisory system for their misalignment. Finger-pointing remains common.

Companies tend to think that investors care equally about each vote on the ballot, cast votes strategically, judge the merits in terms of the firm’s strategy, and value the vote. More often, investors do not see the vote as additive to their long-term performance, triage the few strategic votes and commoditize or defer those seen as immaterial, judge how to vote in terms of their own portfolio’s strategy, and value the option to vote but often not the vote itself.

The system has devolved to a point at which investors and companies simply go through the motions of voting, minimizing the costs that this system creates for them. Companies expect investors to vote, but they generally see the proxy process as a legal obligation rather than an engagement tool. Accordingly, they limit the imposition by devaluing the vote through mechanisms like unequal voting classes, by framing votes as advisory rather than binding, and by limiting annual shareholder meetings to the minimum amount of time and interaction possible.

Investors generally believe that proxy voting does not affect their long-term investment performance in any attributable way, so they limit their efforts. Most asset owners staff the function with a few non-investors, most active managers focus on just a few strategic votes, most index managers are moving toward pass-through voting, and most retail investors do not vote unless they are disgruntled.

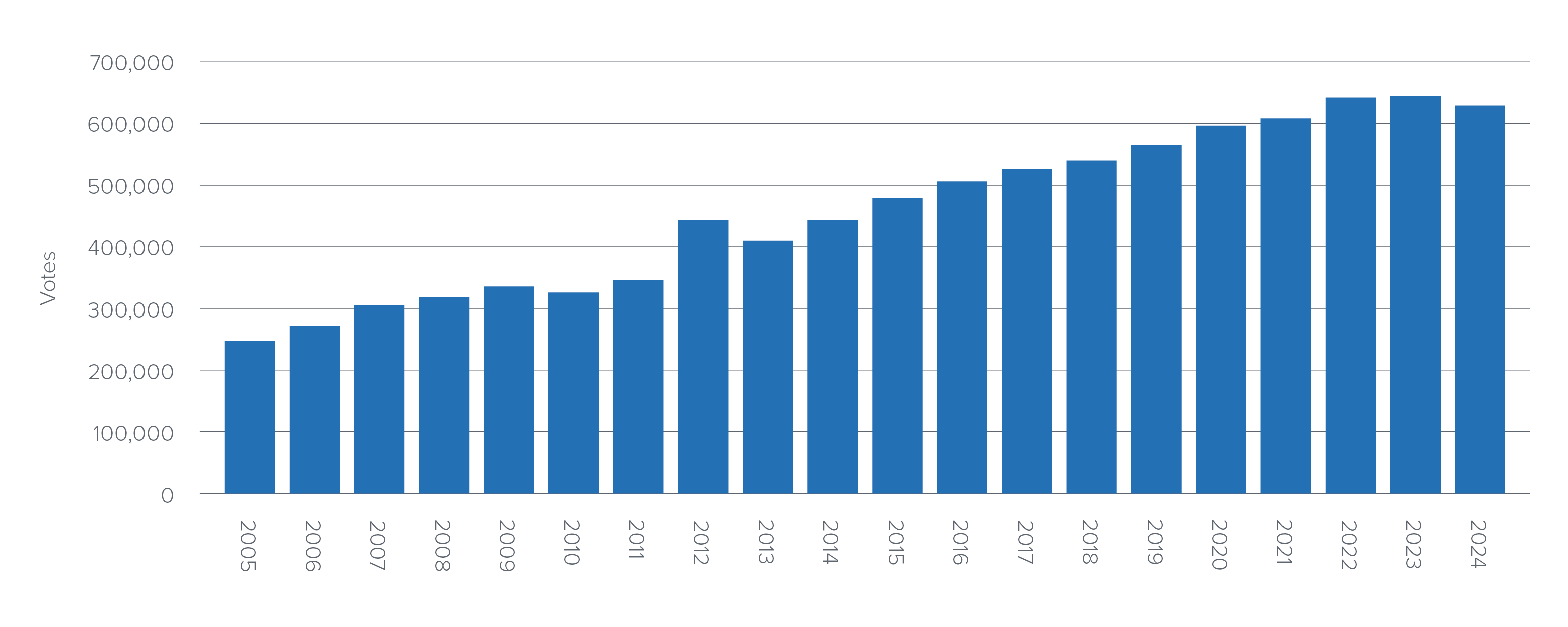

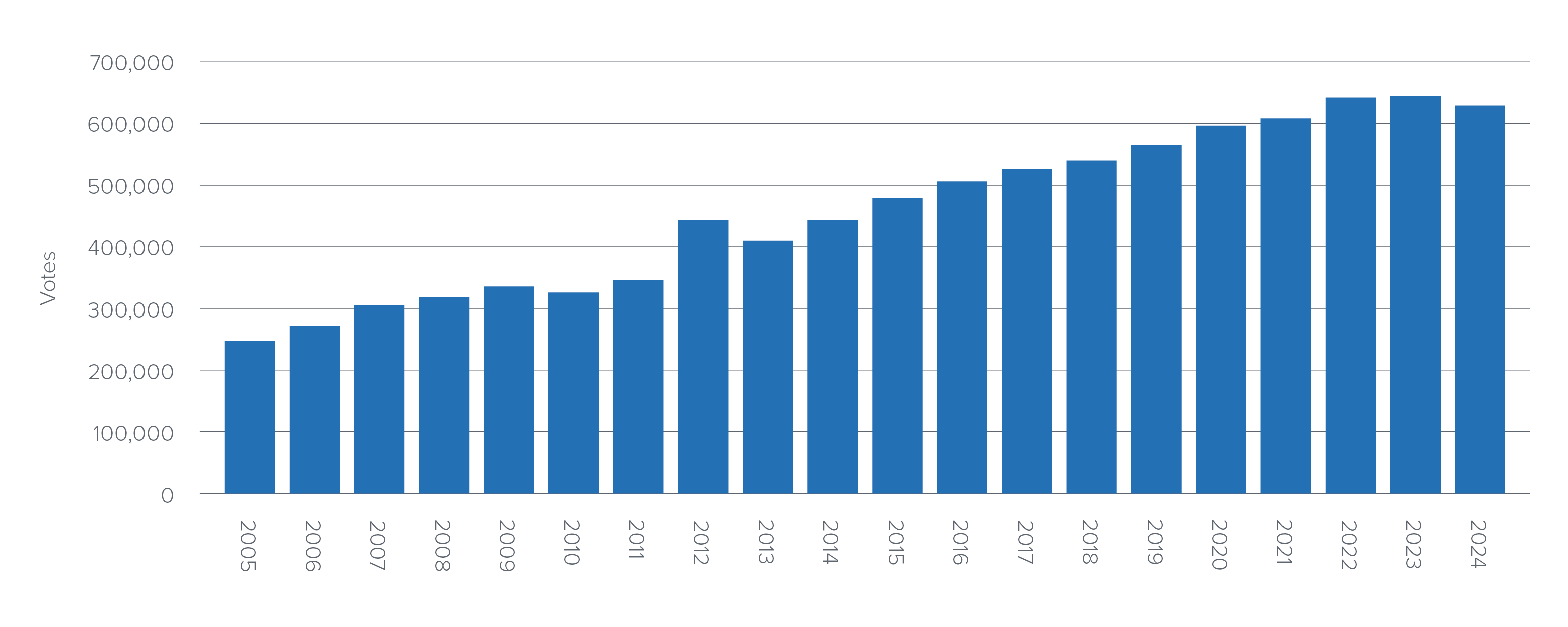

Exhibit 1: Number of votes worldwide covered by ISS

Source: ISS, data provided to FCLTGlobal, November 2024

Both investors and companies blame proxy advisers, but the larger proxy system puts them in the position of being misaligned. Proxy advisers provide a service and have adapted to the demand for that service, which is characterized foremost by its scale. ISS, for instance, issued recommendations covering over 643,000 ballot items worldwide in 2023, the most recent year for which full data is available. That is a 160 percent increase from the 247,000 it covered in 2005, which itself was a mammoth number. Consequently, proxy advisers have specialized in providing a scalable service that fits this volume of voting at the price that clients are willing to pay, even though corporations would prefer much deeper and differentiated analysis of their voting items and, at the executive level, investors may, too.

Global companies and investment organizations can change the proxy system by helping to make sense of the status quo, exploring solutions for healthier alignment, and shifting their behavior focus on long-term value creation.