By Sam Sterling, CFA

The growing disparity between what sustainable investing realistically achieves and what environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investors assume they are accomplishing has been pervasively highlighted in recent regulation, critiques from investors, and in the media. Investors want their backing to come with a promise of value beyond purely financial returns. Sustainable investment funds are predominantly split between those that consider ESG-related risk factors and those that intend to make an impact on those factors – so called “double-bottom-line” impact portfolios. Specifically, these funds are often categorized as:

- Actively Managed ESG Funds

- ESG Index Funds

- SRI Funds

Based on the US Department of Labor non-implementation of their former administration’s ruling on including ESG funds in retirement plans, as well as the forthcoming EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), it seems regulators are on the right track. There are, however, challenges that are unique to different countries’ application of various fund labels, such as the variation between EU countries’ fund labeling (which may be consolidated by the EU SFDR).

The lack of clarity in fund labeling muddles the perception around sustainable investing, driving broader criticism of its perceived failure to deliver societal or environmental benefits. Long-term investors are wise to select funds consistent with their underlying objectives, but that requires a deeper understanding of the nuances behind fund labeling.

Investment Selection Criteria

One of the common criticisms of sustainable investing is about the criteria for investment selection. It is easy to interpret an investment dubbed “sustainable” as an indication that the fund’s investee companies endeavor to advance environmental and social causes. This is due largely to funds failing to clarify their sustainability approach both in their labeling choices and in the prospectus.

Controversy stems from investors being surprised by a fund’s investments, or more pointedly, when they realize the portfolio companies are fundamentally misaligned with investor expectations of what “sustainable” means. As an example, depending on the fund – and the index or benchmark that it tracks – an investor might be surprised by the inclusion of companies in fossil fuels or firearms. The counter-intuitive reason these companies might make it into the portfolio is that they seem ideal when considering the ESG risk factors, compared to companies in the utilities or tobacco industries. The manager will have concluded that investing in these companies would be well within the bounds of the fund’s objective.

The assumption that all sustainable investment funds are the same is clumsy, and one that leaves the door open for further criticism of a useful if not misunderstood sector. The sustainable investing ecosystem is multifaceted. Different types of sustainable funds seek – and yield – different outcomes, though most have one primary goal in common: maximizing returns. The objective is not to reduce carbon emissions or advance diversity directly, but rather through investing in companies with reduced exposure to those risks, they might be achieved indirectly. Such outcomes are in the domain of the socially responsible investment (SRI) and impact funds.

Actively Managed ESG Funds

Active ESG funds apply proprietary analysis of ESG criteria to select their investments. Generally, funds pursuing an active ESG strategy apply the most independent discretion to portfolio composition and – because there is not a common definition of “sustainable” in terms of investing – often have different criteria applied to investments at the discretion of the portfolio managers. The variety of investment selection techniques with this type of fund cannot be understated. An active ESG fund could:

- Use a simple ESG screen – perhaps allowing no issuers rated below an A on MSCI – and then apply traditional fundamental stock analysis for picking from that more limited universe.

- Use a negative screen for certain types of investments – possibly excluding issuers with a majority of revenues from tobacco, oil and gas, or other specific activities – before applying further analysis.

- Incorporate ESG factors into their valuation models and fundamental analysis.

- Do regular fundamental analysis to construct its portfolio but engage actively on ESG topics to drive future value creation.

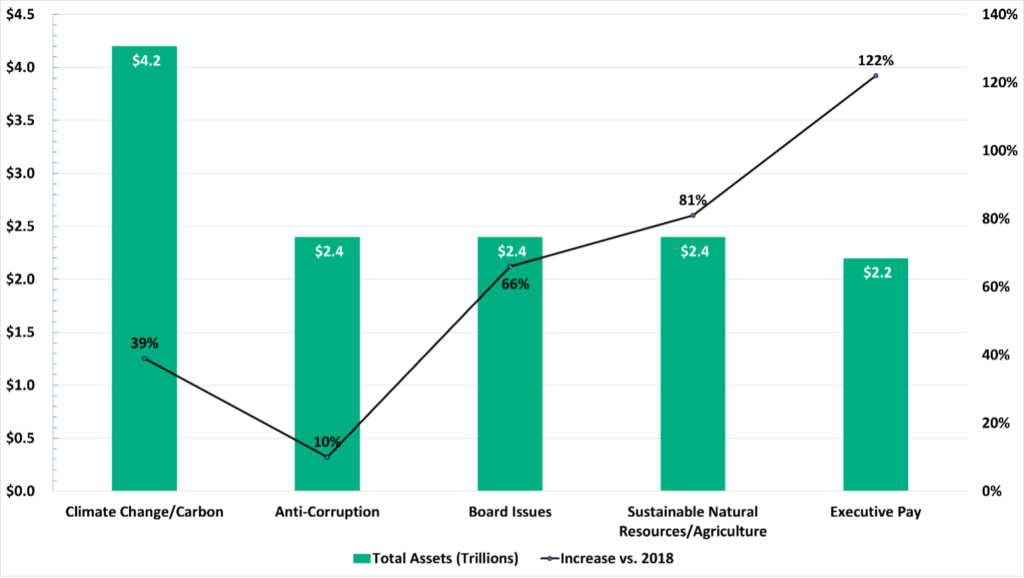

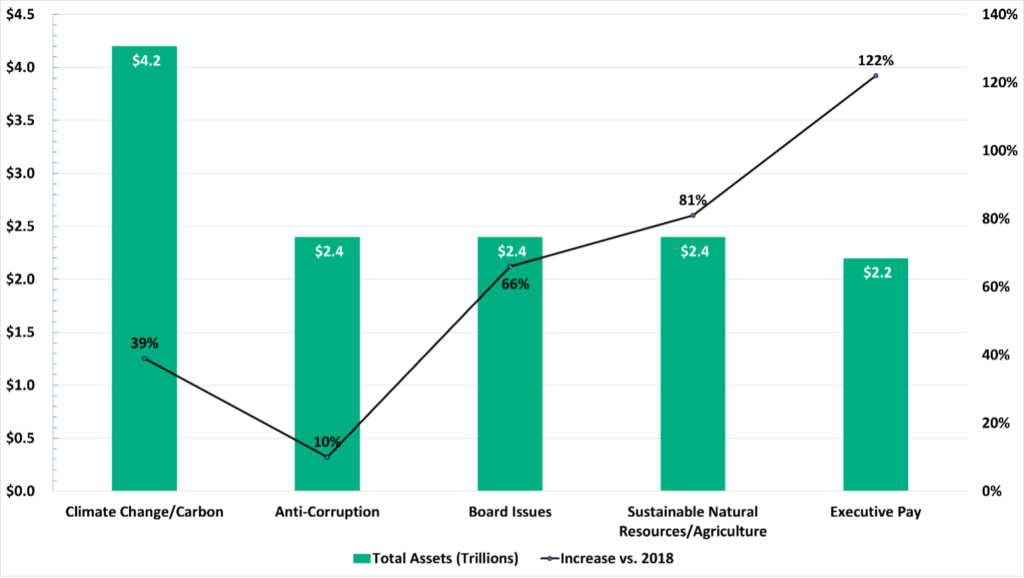

Managers of active ESG funds have a wide range of options, and no two investment managers are likely to apply the same approach. That said, looking at some common sustainability criteria applied, there is a trend in what is most important for active managers:

Most common ESG criteria applied by fund managers by assets, 2020

Source: US SIF

Regardless of the strategy employed, the primary goal of the actively managed ESG fund is to improve returns by incorporating sustainability-related factors to de-risk the portfolio.

ESG Index Funds

ESG index funds construct portfolios that are frequently composed of issuers in indices from third-party ESG index providers such as MSCI, FTSE Russell, S&P Global, and Morningstar/Sustainalytics. Each index has different weighting criteria and metrics for measuring issuer performance, which results in different compositions of the indices. The weightings of an ESG index fund are intended to match the weighting of the fund’s respective benchmark index, so index composition dictates the investment philosophy and investment selection.

Depending on the specific index selected, investee companies in an indexed ESG fund could simply perform well on certain ESG factors. They may also comprise a wide portfolio of stocks but with certain industries screened out – for example, US equities – but not include companies in certain industries like tobacco, oil, and gas, etc.

According to research by MSCI on the top ESG funds, three of the largest indexed ESG funds track indices that are composed through a combination of both methods (negative screens + integration), with slight differences in which types of companies are screened out and which criteria are used to integrate sustainability factors into index weighting.

Like active ESG funds, the overall goal of indexed ESG products is not to influence particular ESG outcomes but to match the performance of the index or benchmark as closely as possible.

Sustainable Impact Funds and SRI Funds

The last category of funds included in the sustainable investing subindustry is impact funds, sometimes called socially responsible investing or impact (SRI) funds. These funds operate to serve a double-bottom line for investors – generating a return, of course, but with equal emphasis on the additional objective(s) of achieving non-financial social or environmental goals, from absolute carbon reduction and climate change prevention to income inequality.

The goals of an SRI or impact fund are often risk factors for the active or indexed ESG funds. For instance, carbon dioxide emission reduction is a characteristic which would be viewed positively by both SRI funds as well as ESG-indexed or active funds. That lower emissions outcome might be the second bottom line goal of the SRI fund, while for the active fund reducing carbon emissions may be seen as reducing risk of regulation or improving a firm’s risk profile by lowering its cost base. Less carbon-intense firms are paying less for energy, which improves the risk/return profile of the firm for active and indexed ESG fund investments. SRI funds may fall outside investors’ ability to apply fiduciary responsibilities that are prevalent in some regions of the world, however new research has also shown there may be a legal framework for applying impact as a criterion in investment selection in many jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Much of the criticism of the sustainable asset management industry stems from a lack of insight into the goals of various sustainable or ESG-labeled funds. Long-term investors select funds that fit their unique financial situation and purpose – they might prefer investments to meet certain criteria (ESG or otherwise) that they consider important to their beneficiaries. If it is within the remit of an investor to address ESG goals – such as climate change, social justice, or others – institutional investors can select the funds that best fit those objectives and clearly communicate them to both external and internal managers and beneficiaries. Clear labeling of ESG products, along with transparency into the investment selection criteria, would go a long way toward assuaging industry concerns.