For public companies, more diverse boards of directors are correlated with significant long-term value. The same can be true for private companies. What role can GPs and LPs play in driving change?

For public companies, more diverse boards of directors are correlated with significant long-term value. The same can be true for private companies. What role can GPs and LPs play in driving change?

By Ariel Babcock, CFA & Victoria Tellez

Research shows that diversity at the board level adds meaningful long-term value for companies and their shareholders. Companies’ efforts regarding diversity within the workforce, or lack thereof, are drawing increasing attention from shareholders, the media, and the broader public. This increased attention is making companies more conscious of their approach to hiring, human resources, and overall corporate culture. This shift is not just for the sake of optics – the data makes a compelling argument that companies with more diverse boards of directors, sourced from a more diverse pool of candidates, perform better in the long run, have greater potential for growth and innovation, and greatly reduce their exposure to risk.

Data from Predicting Long-term Success for Corporations and Investors Worldwide shows that the most diverse boards added 3.3% to return on invested capital (ROIC) as compared to their least diverse peers. And for gender diversity in particular, our analysis found that companies with the most gender-diverse boards outperformed the least diverse in terms of ROIC by 2.6%.

Additional research confirms this trend – a 2015 study from McKinsey & Company found that companies in the top quartile for racial and ethnic diversity are 35 percent more likely to have financial returns above their respective national industry medians, indicating that diversity can be a strong differentiator that shifts market share toward more diverse companies over time. In a separate study, Carter, Simkins and Simpson (2003) examined the relationship between board diversity and firm value for Fortune 1000 firms, and after controlling for size, industry, and other corporate governance measures they found significant positive relationships between a company’s value and the contingent of women or minorities on a company’s board.

In addition to improved performance, diverse boards consistently invest more in R&D and demonstrate an increased capacity for innovation, giving their companies a meaningful competitive advantage. Using a multi-dimensional measure of diversity combining ethnicity, age, gender, education, financial expertise, and prior board experience, Bernile, Bhagwat and Yonker (2017) found that greater board diversity correlates with more consistent investment in R&D projects over time.

A multifaceted team fosters not only creative innovation but resilience, and greater board diversity leads to lower volatility of returns. This is attributed to diverse boards engaging in more consistent and less risky financial policies. Diverse perspectives and ideas keep companies flexible and better able to navigate, or rebound from, unexpected obstacles.

While much of the recent focus around corporate diversity and inclusion has been aimed squarely at public companies, many within the global business and investor communities recognize the need for the private sector to demonstrate progress as well. Yet, comparatively, much less is known about governance and board composition of private equity-backed companies even though they comprise a significant and growing proportion of the economy.

Figures from The Carlyle Group indicate that private companies stand to gain from appointing a more diverse group of candidates to their boards. In a study of its portfolio companies, Carlyle found that firms with two or more diverse board members recorded annual earnings growth 12 percent higher than those with fewer diverse directors.

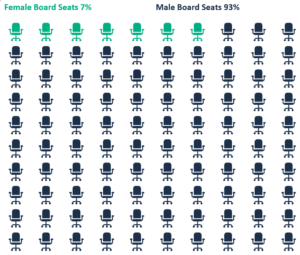

Despite the evidence, progress at private companies has been slow compared to public markets. Gender diversity on public company boards is on the rise in many countries, with the global average at 20%. In comparison, a 2019 Crunchbase study of the most heavily funded private company boardrooms revealed:

Source: Crunchbase, 2019 Study of Gender Diversity in Private Company Boardrooms

Source: Crunchbase, 2019 Study of Gender Diversity in Private Company Boardrooms

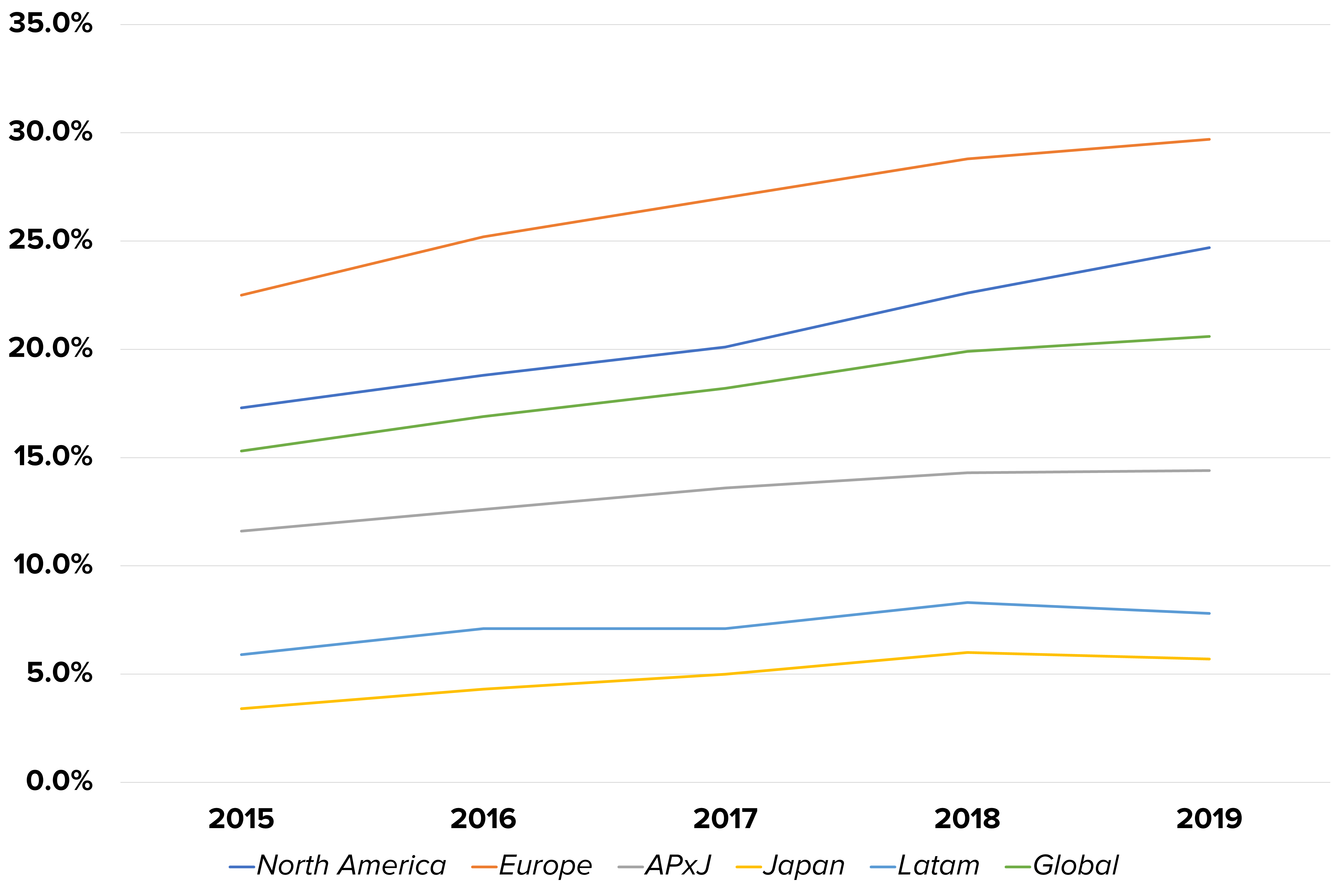

Rather than wait for companies to act, some governments have sought to achieve gender equality on corporate boards through legislation. For example, gender quotas are commonplace in the EU – Spain adopted measures as early as 2007, and France, Italy, and the Netherlands followed suit in 2011. Those same nations boast some of the highest shares of female directors, with France and Norway at 40% and Italy at 33%.

Source: Credit Suisse Research, CS Gender 3000, The BLOOMBERG PROFESSIONALTM service

Source: Credit Suisse Research, CS Gender 3000, The BLOOMBERG PROFESSIONALTM service

More recently, the U.S. has closed the gap. In 2018, California was the first U.S. state to require its publicly listed companies to appoint women to board positions. Depending on company size, the bill requires at least two to three female board members by year-end 2021.

As policymakers work to legislate the issue, other independent organizations are putting similar guidelines in place. Goldman Sachs announced in 2020 that it will only IPO companies in the US and Europe that have at least one diverse board director (it has since been determined that this will increase to two in 2021). NASDAQ filed a similar proposal with the SEC to adopt new listing rules regarding board diversity. The new rule would require companies listed on Nasdaq’s U.S.-based exchange to meet minimum standards for board diversity or otherwise explain their non-compliance and publicly disclose consistent, transparent diversity statistics regarding their board of directors.

The evidence is clear – diversity among a company’s leadership presents distinct advantages. However, the advantages in of themselves have not compelled companies to action. The pressures that come with being a public company – the same pressures that can sometimes drive short-term decision-making – have in large part driven improved diversity and inclusion, especially at the board level. But in the private sphere, absent the involvement of shareholders or regulators, a great deal of responsibility rests on companies’ private equity owners. There are key steps private equity firms themselves can take to meet this responsibility.

In order to make private boardrooms more inclusive, private investors must first assess their current practices and the role they can play in progress. Frank discussions between general partners (GPs) and limited partners (LPs), both in the diligence process and post-investment, can help both sides leverage their positions to enhance diversity and inclusion at the portfolio company level.

Once this initial evaluation has been made, the actual implementation of next steps is critical. Rather than resting on the laurels of loose commitments and vague targets around board diversity, grounding a plan in real-world, practical actions is a more direct way for GPs to play a role in real change, supported by their LPs.

Finally, and some would argue most importantly, accountability and reporting are required to ensure that private equity firms are hitting their portfolio-company diversity-related goals. A framework that tracks the status of current voting and non-voting portfolio company board directors and board chairs, as well as changes resulting from director turnover, can serve as a baseline for creating consistent information sharing between GPs and LPs.

To improve in each of these areas, FCLTGlobal has convened numerous roundtables over the course of the past year. The output of these sessions will be practical guides that both GPs and LPs can use to evaluate, implement, and report on diversity and inclusion in the boardrooms of their privately held portfolio companies. For some firms, these may be the first steps. For others, they may be a refinement of plans already in motion. Regardless, they are a means to putting leaders in the boardroom of private companies who are representative, forward-looking, and positioned to create long-term value.